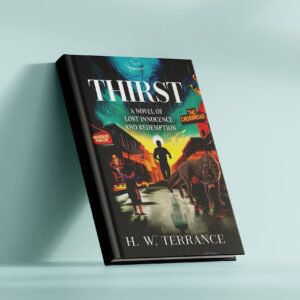

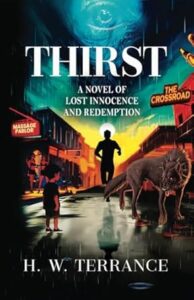

Thirst by H. W. Terrance

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

In  2024, we were contacted by the son of an author we had previously worked with. His message was simple but striking:

2024, we were contacted by the son of an author we had previously worked with. His message was simple but striking:

“I have a real close friend who’s been sober for over 30 years. His story is unlike anything I’ve heard. You need to meet him.”

That introduction led us to H.W. Terrence—a man whose journey would challenge us, change us, and ultimately shape one of the most powerful books we’ve ever taken on.

From the moment we spoke with Terrence, we were struck by his charisma. His energy was palpable, and his conviction undeniable. He wasn’t just sharing his recovery; he was sharing a belief—a belief that if he could overcome his demons, anyone could. He didn’t just want to tell his story; he wanted to give hope. “If I could recover, anyone can,” he said, his voice steady, but full of raw emotion.

It was clear to us that this wasn’t just another memoir. Terrence had the gravity of someone who had clawed his way back from the edge—and carried the weight of what it cost him. He spoke of sleeping on the streets. Losing his home. Losing his children. Being invisible. “I’ve been that guy people step over,” he said. “I know what it means to disappear.”

It was the kind of conversation you don’t forget.

We saw a unique memoir instantly. But as we pushed the author to begin writing, we saw a surprising shift. The more we encouraged him, the more withdrawn he became. Our usual methods of Interview Into Writing did not work. Our empathy and reflecting back to the author his thoughts—didn’t seem to strike a chord with Terrance. Instead, he became more hesitant, eventually saying, “Never mind.”

The story went still.

This was not the first time Terrance stalled on the project. Later he admitted to have started it several times over the years. Each time he stopped. Each time he would get stuck after a few chapters.

We didn’t give up on Terrance. His story was to harrowing to be dropped. We wanted for him to write the book so that we could recommend it to others.

Yet Terrance didn’t budge. For a man who’d spoken freely at AA meetings for thirty years, there was a fear when coming to putting it in print—the stakes were high. The fear of being exposed too sharp.

MAYBE FICTION INSTEAD

We decided to step sideways.

What if it wasn’t a memoir? What if it were a novel? What if it was fiction, into which he could weave his personal story, thinly veiled yet deeply felt?

This idea sparked a shift. Terrence became open to the concept of a novel, though he requested that the author remain anonymous. We agreed, if only for a time, wanting to get the book going. We wanted to see words on page, knowing that eventually we’d have to encourage the author to sign his own name rather than keep his identity anonymous.

We began working using our unique Interview-Into-Writing method, a cornerstone of our approach at YourBookTeam. We scheduled lengthy sessions with him, attentively listening to his stories and ideas before carefully paraphrasing them in writing. Our intention was to preserve and amplify his authentic voice throughout this process. After several productive sessions, we edited the first few chapters, polishing the prose and tightening the narrative structure. However, when we shared these edited versions with him, his reaction caught us off guard. “This isn’t me,” he said firmly, his disappointment evident.

And he was absolutely right. As we revisited his original drafts, we discovered that Terrence’s writing voice was already exceptionally mature, perhaps one of the most naturally developed we had encountered in our years of publishing work. His style was distinctive—minimalist, direct, and precise, bearing a striking resemblance to Hemingway’s economical approach to language. In comparison to our edits, in his own words there was no excess, no unnecessary flourish; each word served a clear purpose within his narrative.

What became immediately apparent was that Terrence knew precisely what he wanted to say, and, more importantly, he had an innate understanding of how he wanted to say it. His sentences carried a rhythmic quality that couldn’t be taught, a natural cadence that many writers spend decades trying to develop. The sparse dialogue, the measured descriptions, the strategic silences between thoughts—all revealed a writer who had already found his voice without needing our stylistic intervention.

Preserving the Author’s Voice

This realization prompted us to completely recalibrate our approach. Rather than acting as developmental editors who might reshape his prose, we needed to function more as literary caretakers—preserving his distinctive style while addressing only the most technical aspects of the manuscript. We shifted our focus to ensuring consistency, catching minor grammatical issues, and occasionally suggesting structural adjustments that would enhance his existing narrative without altering its fundamental character.

Our main goal became staying out of his way, while gently encouraging his creative genius without imposing our editorial presence in ways that might slow or disrupt his natural flow. This meant establishing a different kind of working relationship—one based on minimal intervention and maximum support. We created a streamlined feedback process, technically sharing our screen during sessions while he dictated changes. We became his hands on the keyboard. He spoke, we typed. No embellishment. No smoothing. And what came through was striking: a sparse, brutal, lyrical voice.

He was razor-specific. If we changed a single word—“a” instead of “the”—he’d catch it. “I wouldn’t say that,” he’d insist, teaching us an invaluable lesson in style. For Terrence, this meant being incredibly attuned to his voice, ensuring we did nothing that might disrupt the authenticity of his narrative. Terrence didn’t want a ghostwriter—or anyone shaping his voice into something more polished or palatable. He needed to sound like himself: raw, direct, and completely unfiltered. There was a signature to his sentence structure we could not imitate. So we let him lead. It took more hours, but it was absolutely worth it.

When the manuscript was complete we gave it to our beta readers. The reviews were very positive. Yet there were some scenes that required expansion. One scene in particular—the main character’s children watching as police took him away—was too short. The beta readers—and we, too— wanted it expanded.

At first, Terrance would not have it. He wanted to get the book published and was “sick and tired” of working on it. In truth, it was too painful for the author to revisit that memory. But weeks later, after trust had deepened, we met, and he dictated a moving, harrowing scene, line by line.

After months of work, the story felt nearly complete.

En Media Res

We still had one final edit to the story, though. When we shared the manuscript with more beta readers, they felt the book truly began clicking after the first section about the childhood, when the character reached his teenage years. We were told that the childhood sections weren’t as compelling and did not have the high stakes that the addicted teenager had.

Terrence insisted that childhood was essential to understanding the character’s journey, and we agreed. Yet, the beta readers’ feedback was important to us. How could we get the angst from the teenage years earlier? We were afraid of losing readers, of readers puting the book down after a couple of chapters, thinking the book was about a child.

Then Terrance came up with a unique prologue idea. “Start with the arrest,” he suggested. The scene where he’s seventeen, in a cell, facing the consequences of his addiction. We got to work. We wrote together a prologue. The shift was electric.

This “in medias res” approach—beginning in the middle of the action—transformed the entire manuscript. Opening with seventeen-year-old teenager in a jail cell, shaking with withdrawal and facing serious charges, immediately grabbed readers by the throat. The raw intensity of that moment—described in Terrance’s signature sparse style—created an emotional anchor that colored every subsequent page. Readers were invested from the first paragraph, desperate to understand how this young man had arrived at such a devastating point and what would become of him afterward.

The childhood scenes that followed took on new meaning when viewed through the lens of that arrest. What might have seemed like ordinary childhood memories were now shadowed by the knowledge of where they ultimately led. Each early experience, each family dysfunction, each moment of neglect and trauma now carried the weight of inevitability—small stepping stones on a path leading directly to that jail cell.

Structurally, this approach allowed us to create a more dynamic timeline, weaving between present consequences and past causes. This technique gave readers two entry points into the story and created an arresting beginning to what might otherwise have been a slow-burner.

Perhaps most importantly, starting with this crisis point honored what Terrance had been telling us all along—that moments of severe consequence were often necessary catalysts for change. By structuring the book around this pivotal scene, we not only created a more compelling reading experience but also stayed true to the emotional truth of his journey.

Struggling with the Title

Once we nailed the manuscript, we still were left without a title. At first, the title was “Long Time Running”

based on the song by The Tragically Hip.

But our beta readers told us that title didn’t work. It failed to capture the raw intensity and struggle that defined Terrance’s addiction and recovery journey. Though it referenced endurance and persistence, it lacked the visceral, immediate quality that would reflect his distinctive minimalist writing style. The song reference to The Tragically Hip, while meaningful to Terrance, did not resonate with the broader audience or convey the book’s core themes effectively.

We tried new titles. Based on the novel’s three distinct phases: the boy, the hound, and the man, we came up with “The Boy and the Hound.”

But that title didn’t work either. Our beta readers and editors said that it sounded too much like a children’s story or coming-of-age tale, which drastically misrepresented the harrowing, adult nature of Terrance’s addiction narrative. They worried potential readers might expect something lighter or more whimsical, only to be confronted with the brutal reality of alcoholism, homelessness, and family separation. The metaphorical “hound” of addiction required too much explanation and didn’t immediately communicate the visceral struggle at the heart of the story. We were lost as to the title.

coming-of-age tale, which drastically misrepresented the harrowing, adult nature of Terrance’s addiction narrative. They worried potential readers might expect something lighter or more whimsical, only to be confronted with the brutal reality of alcoholism, homelessness, and family separation. The metaphorical “hound” of addiction required too much explanation and didn’t immediately communicate the visceral struggle at the heart of the story. We were lost as to the title.

Finally, much like in the writing process, led by the author himself, the title too came directly from the author. Terrance came up with the short title “Thirst”.

The title Thirst proved most effective because it directly evoked both the physical craving of addiction and the deeper spiritual longing for recovery. This single, powerful word created an immediate visceral response that aligned perfectly with Terrance’s sparse, uncompromising prose style. It communicated the core of his experience without explanation or elaboration—exactly matching his approach to storytelling. When we presented “Thirst” to our beta readers, they immediately connected with it, saying it captured the essence of the novel: that constant, unrelenting need that drove the character’s darkest days and then continued to inform his recovery later.

Now we had the title. We built everything around it.

The subtitle—A Novel of Lost Innocence and Redemption—emerged naturally.

The Final Product

Reflecting on the success of the novel, we can clearly see that the author was fully dedicated to telling his story. Terrence gave everything to the project. And in the end, Thirst became more than his story—it became his offering.

Terrance is now embarking on the next chapter of his journey with us—Quest—a sequel, offering an exploration into the depths of resilience, self-discovery, and the unrelenting pursuit of grace.

As we support him in shaping the manuscript, we’re also leading the charge in getting his message out: from guest appearances on powerful podcasts like The Chris Voss Show and Don’t Hide the Scars, to bold, unconventional social media campaigns.

Final Thoughts

Looking back to that first striking message—”I have a real close friend who’s been sober for over 30 years. His story is unlike anything I’ve heard. You need to meet him”—we now understand the profound truth it contained. When we first encountered Terrance, we were moved by his charisma, his energy, and his unwavering belief that his story could give others hope. What we couldn’t have known then was how deeply his journey would challenge and change us as publishers. From the initial resistance to the surprising pivot to fiction, from discovering his natural Hemingway-esque voice to witnessing the power of his “in medias res” opening, every step of creating “Thirst” reinforced what Terrance told us in that very first meeting: “If I could recover, anyone can.” His words, once simply a statement of personal conviction, have now become a powerful message reaching new readers daily, proving that sometimes the most transformative stories are the ones that almost went untold.